Case Study on the Harshness of Singapore Drugs Laws. The drug laws in Singapore are the strictest in the world. Kim* is a young professional who started using cannabis during a tumultuous family period. She was on an upward trajectory, but she continued to use cannabis throughout this period. She made friends with people who use cannabis and was often buying cannabis for her friends for free. But life took a dramatic turn when one of her friends got caught by the police and pointed Kim as the supplier.

Penal Sanctions

Singapore has no mercy for its people; just 15 grams of marijuana would be the basis of assuming trafficking activity, which might result in a death penalty for exceeding 500 grams. No death penalty will be delivered to Kim, but an equivalent of at least five years in jail will be doled out for her wrongdoing, while it may have reached the upper limit that is, up to twenty years in jail. Her friends were instead treated as drug users rather than traffickers and received a different outcome: six months of compulsory rehabilitation at a state-run facility.

Drug Rehabilitation in Singapore

The DRC operates like a prison and places an emphasis on a deterrent regime rather than therapeutic comfort. Inmates live in deplorable conditions, in shared cells with little to no privacy or amenities. The DRC emphasizes education programs that would encourage inmates to abstain from drugs, as many of its inmates are first-time and second-time offenders.

Although much has been debated about the efficiency of Singapore’s zero-tolerance policy, which used to consider drug use purely a criminal matter and never as a health concern, there is evidence of new approaches being taken lately. Rehabilitation frameworks are increasingly encompassing more psychological support and counseling from the government.

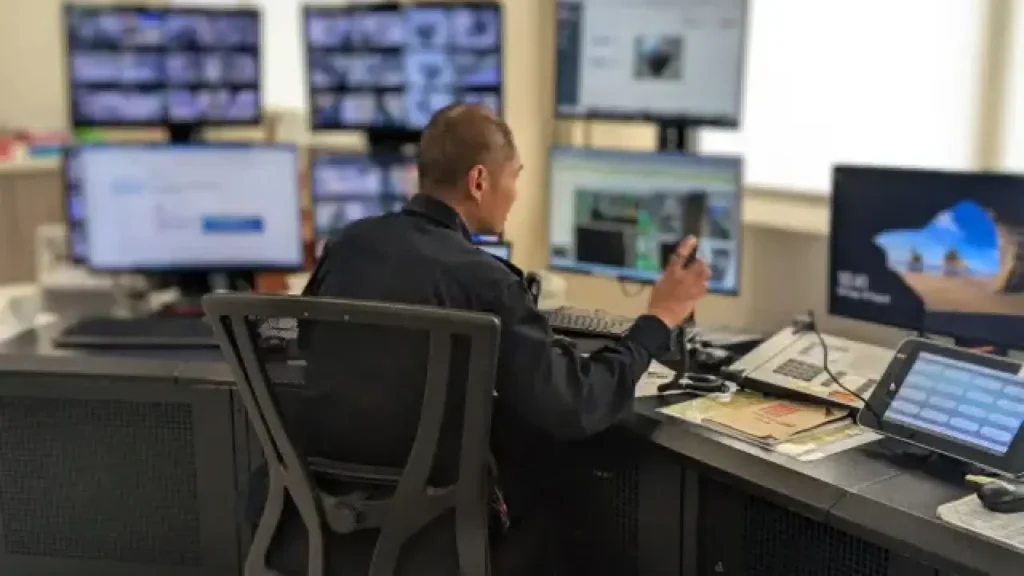

Surveillance and Support after Release

Detainees are controlled as closely as possible once they are released from the DRC and are usually kept sober, either through electronic tagging. The government has made some efforts to reintegrate ex-users into the community; however, the system is criticized for retaining aspects of degradation and not remedying the roots of dependency.

While a rehabilitative approach has been practiced on drug users, traffickers are given grave punishments as the state remains merciless in its policies towards drug crimes.

Kim’s case points to serious consequences that drug laws entail in Singapore, particularly for the people who happen to find themselves within its system that makes a rather sharp difference between user and trafficker. She waits for her judgment with the uncertainty of her future over her, reflecting the deeper problems of people caught within the strict net of Singapore’s drug policy.